Code != idea

(The original title and description of the talk changed between the pitch and final version, hence the differences.)

This is a lightning talk I gave at the satRday 2018 conference. In it, I share an epiphany I had about programming and how it relates to people and our ideas, after programming for most of my life and discovering higher-level languages like Python and R. The talk won best student lightning talk, which included a copy of the beautiful R for Data Science signed by Hadley Wickham himself!

Fast forward 4 years, and this realisation doesn’t feel as profound as it once did, but that’s okay. I believe the world would be a little better if everyone shared their personal learnings and experiences.

Anyway, keep scrolling for a written version of the talk.

My journey from Game Maker to Python

Good morning everyone, my name is Wasim.

A little background. I started programming when I was in primary school. I’ve always loved games, and making things. Unsurprisingly, my foray into programming started with making games.

After vigorous searching for game making software, with my favourite search engine at the time, AltaVista, which some of you may remember, I found a program called Game Maker.

It had a GUI, where you created game objects and programmed logic into them with buttons. It also had scripting capabilities. But I didn’t dare to delve into them.

Eventually, a cousin of mine introduced me to a more powerful tool. A programming language called DarkBASIC, a form of the language, BASIC.

It had a nice editor, a built-in command line interface. I think the 1 and 2 on the top right corresponded to tabs. And it allowed you to create 3D games.

I then moved on to some of the more “real” programming languages. I dabbled in C++.

I was taught Java in high school.

And finally, I settled on Python. I think the reason I hopped so often from one language to the next, was because I was never quite satisfied with how it “felt” to program in these languages. I was never truly comfortable with the way I had to translate what I thought into what I typed. Until Python.

The joy of high-level languages

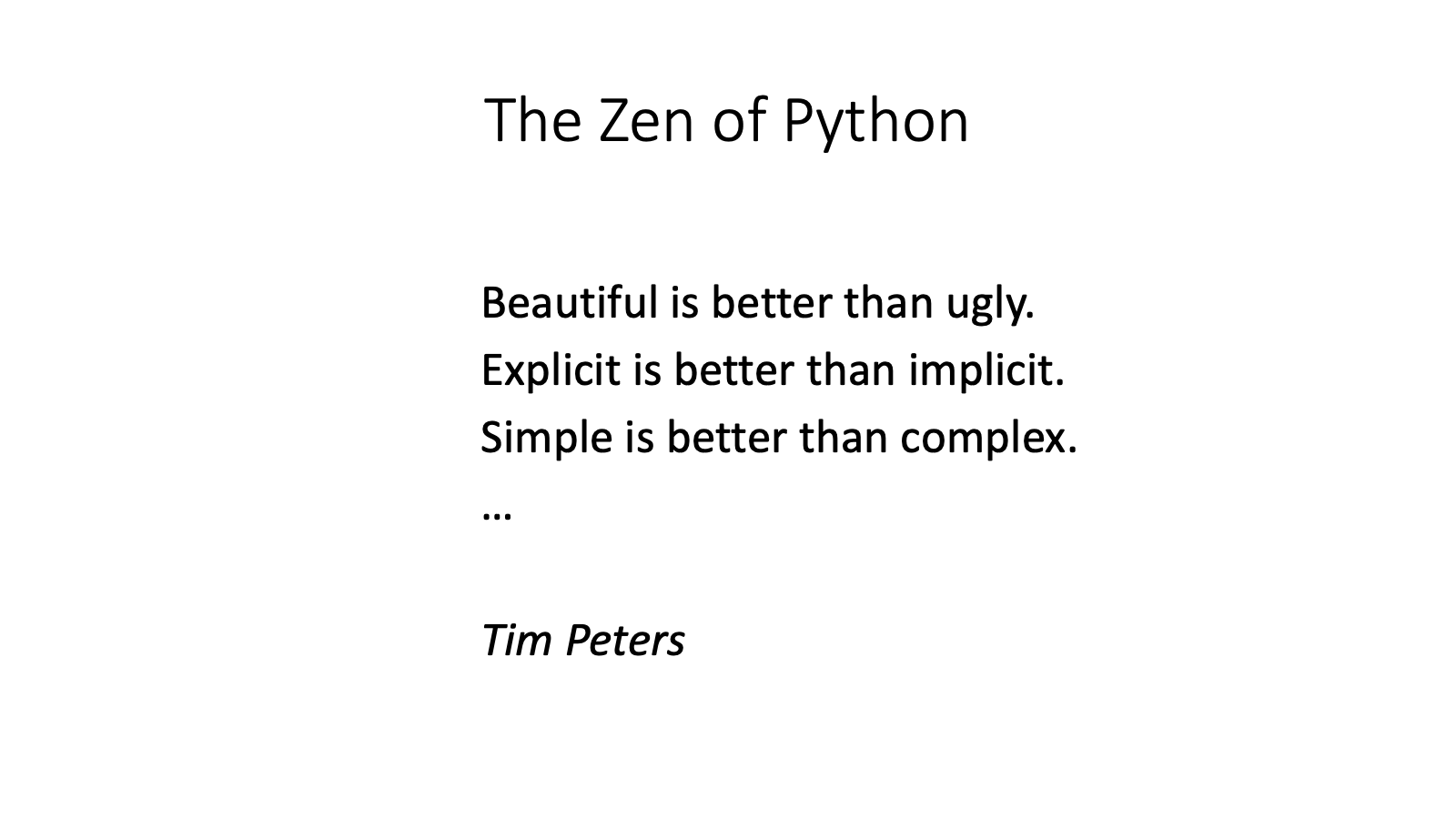

With Python, I learned about writing and reading beautiful code. If you haven’t already seen this poem, The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters, you should check it out.

There is an idea called writing “Pythonic” code, which this poem sort of defines. There was something compelling, almost poetic, about reading and writing “Pythonic” code.

As a young programmer, it was the first time I realized the importance of how code looks, not just what it does.

This is not a pipe

More recently, I came across an even more interesting idea about how code looks.

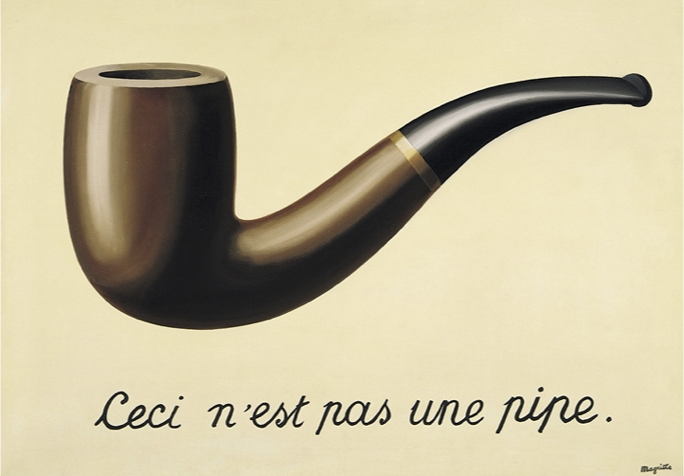

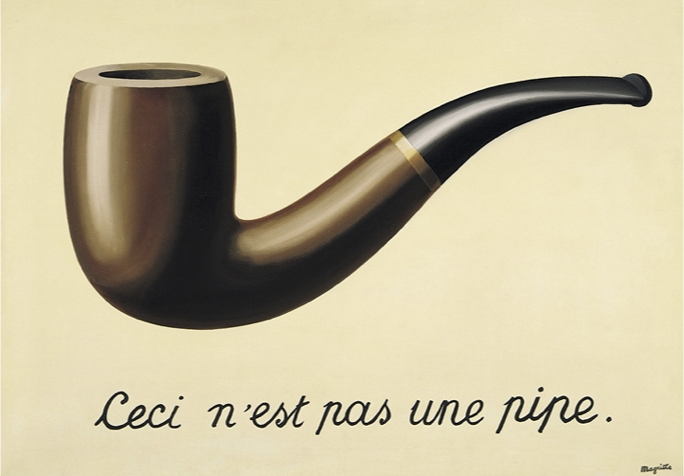

Here’s a painting, by the French artist, René Magritte, that captures the idea. The text at the bottom translates to “This is not a pipe.”

If you haven’t seen this before, that might be a little confusing.

“That is a pipe. I’ve seen pipes before, and that, my friend, is a pipe.”

Well, you can’t pack this with tobacco and smoke it. This is a painting of a pipe, an image, a representation, but its not the pipe itself.

At this point, you might be wondering: What does this have to do with code? And what does this talk have to do with R?

Well, just as this is a representation of a pipe…

This is not an idea

This is a representation of an idea. The code is not the idea itself.

I believe that when we code (even for experts) we constantly struggle translating between our idea and its representation. If the code is a particularly good representation of our underlying idea, then it flows seamlessly, almost by itself.

On the other hand, if the code is not a good representation of our idea, then this struggle is quite costly.

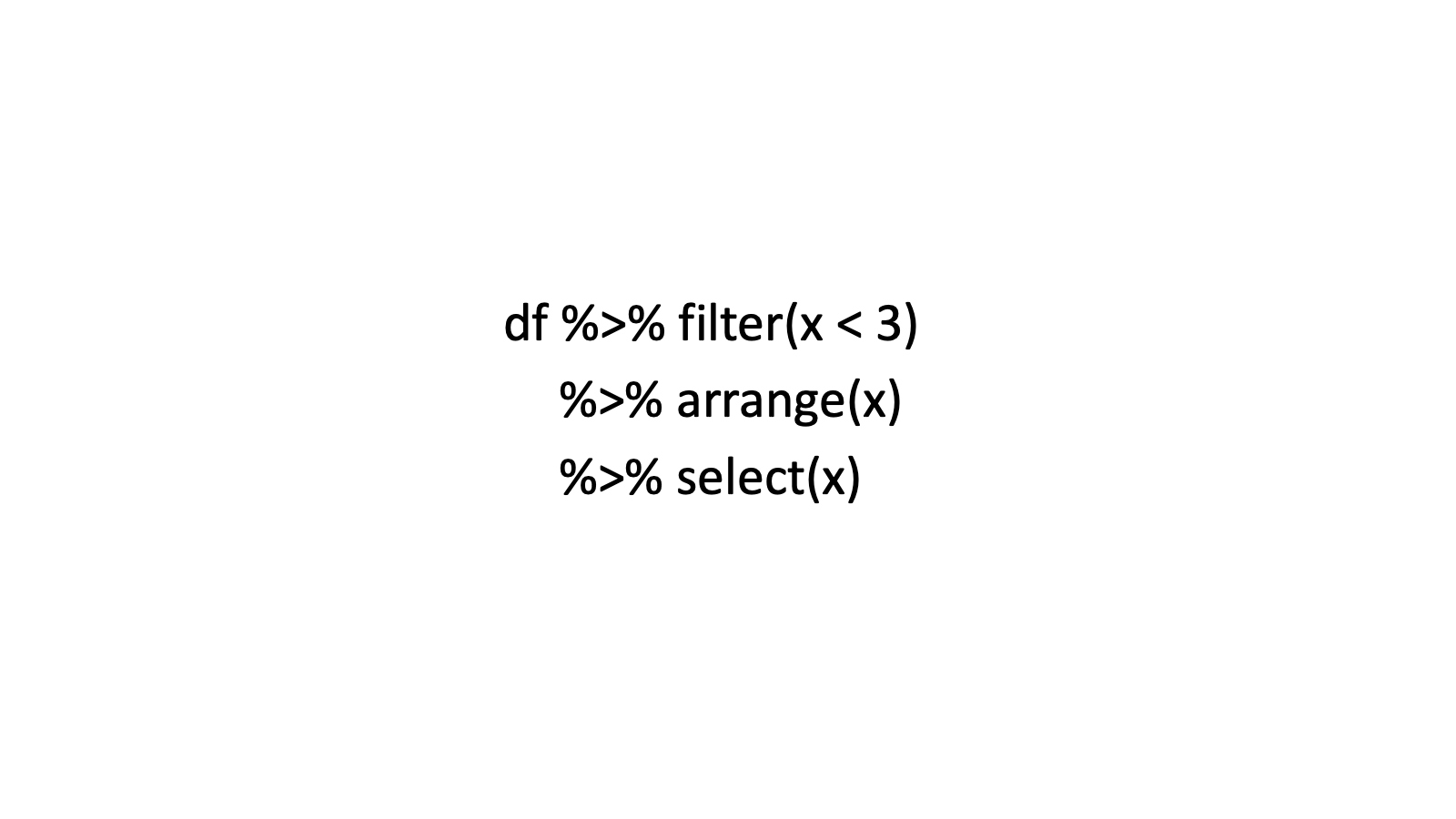

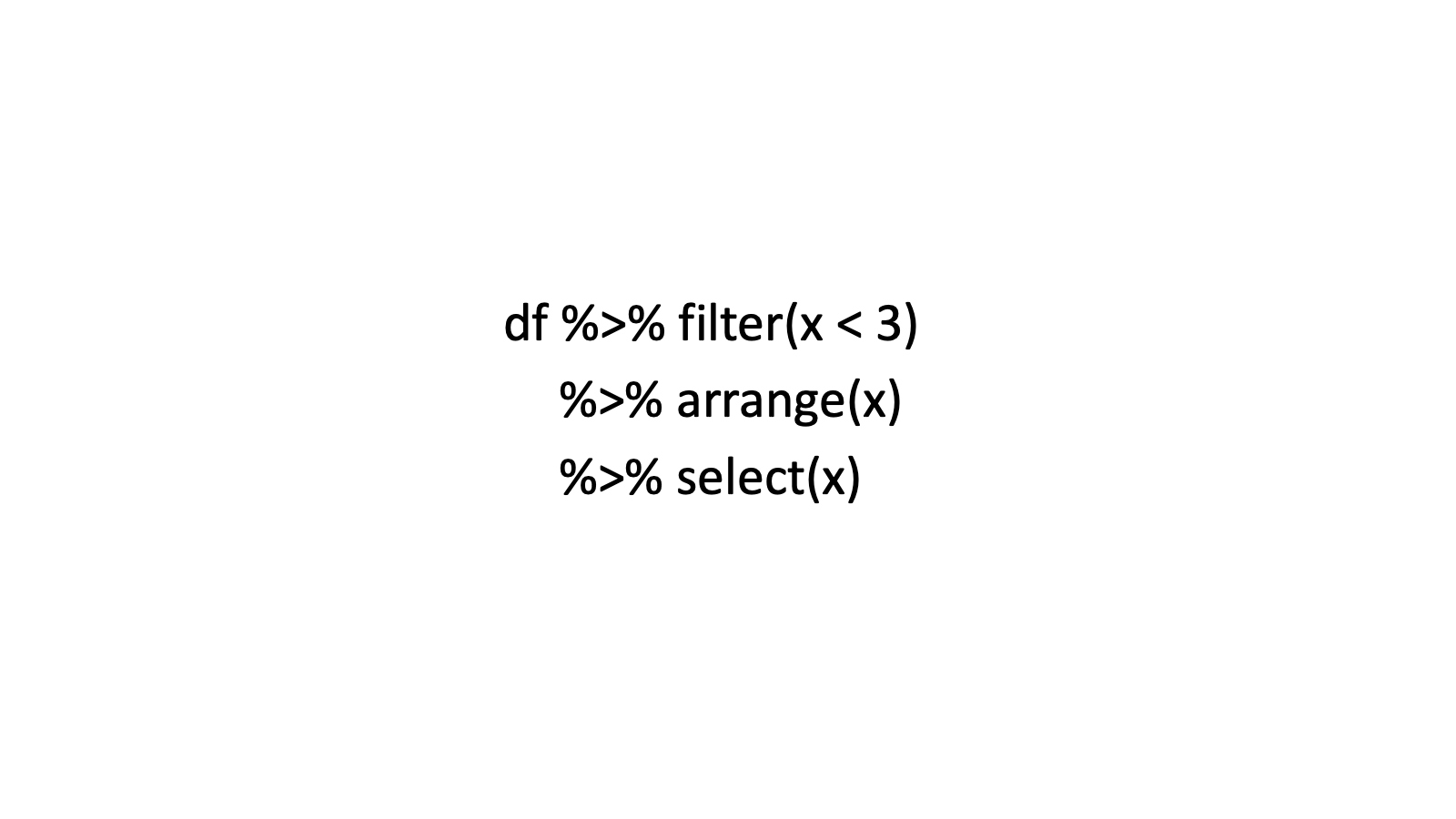

I wanna show you, by example, why I’m so fascinated by R. This is some very simple dplyr code.

What I do when I read (or write) code like this, is to translate it to and from English. I don’t think “df percent greater than percent…”

Translating code to idea

I might start off by thinking that I want to “Take df”, in order to do something to it.

I’d read the pipe symbol %>% as “then”.

I then want to filter “rows of df where”

Read the symbol as “is less than”

Replace the pipe symbol with “then” again

I then want to arrange rows of df by…

Same thing with the pipe symbol.

And finally, I want to select the column…

And, very easily, we have an English sentence.

Oh! And if we’re really fussy, we could add punctuation.

So we’ve translated, very easily and systematically, from dplyr code to English.

Isn’t that a beautiful representation?

It’s beautiful because it’s been so carefully designed, functions have been so carefully named, all keeping in mind one very important principle:

Code represents the ideas of people

Code represents the ideas of people. By considering the people who will use it, we minimize the cost of translating from obscure machine-friendly commands into beautiful prose.

And by minimizing this cost, it frees our minds to focus on what’s really important: the ideas themselves.